Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common pathologic clinical arrhythmia lasting more than 30 seconds, and its incidence and prevalence continue to increase. It has been estimated that 5.9 % of patients aged >65 years suffer from AF.1 In the Rotterdam study, 17.8 % of patients over 85 had AF.2 The lifetime risk for developing AF in both men and women above age 40 is one in four.3 This arrhythmia, with its attendant comorbidities, poses a substantial physical, psychologic, and financial burden on the populace and is a significant public health concern. Evaluating and managing AF appropriately at the primary care level (by minimizing risk factors) and recognizing and treating the arrhythmia immediately will play important roles in containing this epidemic. This review article addresses the recognition of AF and the importance of distinguishing it from other arrhythmias with an irregular pulse. It discusses the available options for stroke reduction and examines the correlation between symptoms and rhythms. It then reviews existing and potentially novel approaches to rate and rhythm control and their role in controlling symptoms in patients with AF.

Types of Atrial Fibrillation

The type of AF determines treatment, and we will use the definitions from the most recent American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS) guidelines on AF from 2014.4 Paroxysmal AF (PAF) terminates spontaneously or with intervention within 7 days of onset. Persistent AF lasts >7 days and often requires pharmacologic or electrical cardioversion. Long-standing persistent AF lasts >12 months. This is an important change to the definition since cardioversion and ablation success rates diminish substantially in patients with long-standing persistent AF. Permanent AF describes the situation where the patient and physician have decided to stop pursuing a rhythm control strategy.

Confirming the Arrhythmia

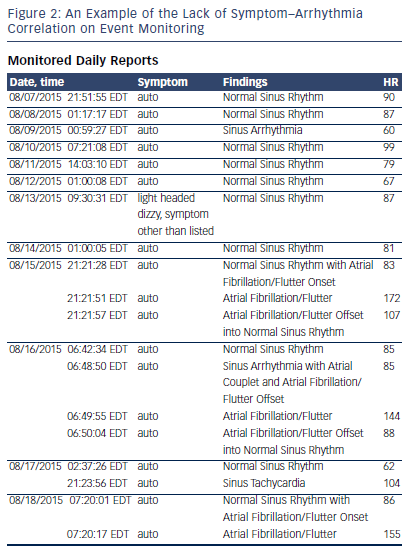

The most common clue for suspecting that a patient may be in AF is the irregularity of the pulse. As medical students, we are all taught to associate an “irregularly irregular” pulse with AF. However, there are several arrhythmias that can produce irregularly irregular pulses and a few that produce regularly irregular pulses, which can also feel irregularly irregular if they have not been assessed for an adequate period of time. Irregularly irregular pulses are present in AF, atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular (AV) conduction, wandering atrial pacemaker, multifocal atrial tachycardia, and frequent premature atrial and ventricular complexes. Regularly irregular pulses may be noted in patients with sinoatrial exit block as well as second degree AV block. If the pulse is not monitored for an adequate interval the pattern of irregularity may not be perceived, and a wrong conclusion may be drawn.

An electrical rhythm strip is still the only reliable way to identify these arrhythmias. Patients now have access to home blood pressure (BP) monitors, pulse oximeters, and single lead rhythm monitors, which indicate the presence of irregularity.5,6 This does not constitute proof of AF. Even computer-based ECG diagnostics frequently get the above arrhythmias confused, and simply reading the verbal report of an ECG without looking at the rhythm strips for oneself will result in an erroneous diagnosis (see Figure 1). Implanted pacemaker and defibrillator diagnostics can also confuse supraventricular tachycardia with AF or atrial flutter and simply using the presence of atrial high rate (AHR) episodes from a pacemaker check as proof of AF is not appropriate. The stored electrograms need to be evaluated to confirm the arrhythmia before treatment can be suggested.

Based on present knowledge, only AF and atrial flutter pose a significant stroke risk and require risk-factor-based anticoagulation. Also, the treatment for typical atrial flutter (counterclockwise isthmus dependent flutter) is significantly different from the treatment of AF since typical atrial flutter can be ablated relatively easily with excellent success rates (90 %). The clinician is obliged to offer patients the appropriate treatment choices based on risk and efficacy, and identifying the correct arrhythmia is the first step.

Evaluating and Treating Stroke Risk

Once AF has been confirmed, estimating a patient’s stroke risk in AF is paramount, as an embolic stroke due to inadequately treated AF is the surest way to negatively impact quality of life (QoL) in these patients. Several algorithms have been developed over the past 25 years and the CHA2DS2-VaSc scoring system has been most recently validated.7–9 With nonvalvular AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 (i.e., aged <65 years with lone AF), both the US and European guidelines agree that it is reasonable to omit antithrombotic therapy. However, the two guidelines differ in their recommendations for patients with a CHA2DS2-VaSc score of 1. The US guidelines allow for antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, or neither, based upon an assessment of the risk for bleeding complications and patient preferences; whereas the European guidelines recommend anticoagulation as the only option. Both guidelines agree that at a CHA2DS2-VaSc score of ≥2 anticoagulation should be instituted.4,10 Warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban have been approved for this use. Patients who are intolerant, or have a contraindication, to the use of anticoagulants would be candidates for a left atrial appendage occlusion, whose efficacy has been validated recently.11

Symptoms Related to Atrial Fibrillation

Patients may present with a variety of symptoms related to AF. The most common symptoms include palpitations, dyspnea, and fatigue. Additionally, chest pain, lightheadedness, presyncope, and syncope may be also reported. More than half of patients with AF experience a decrease in exercise tolerance defined by lowered New York Heart Association functional class. In addition to simple awareness of having an irregular rhythm, there are multiple potential mechanisms for these symptoms, including loss of atrial contraction, loss of AV synchrony, bradycardia, tachycardia, or even tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy. Understanding the type of symptom and the mechanism behind it are important steps in determining the optimal treatment strategy for patients with AF.

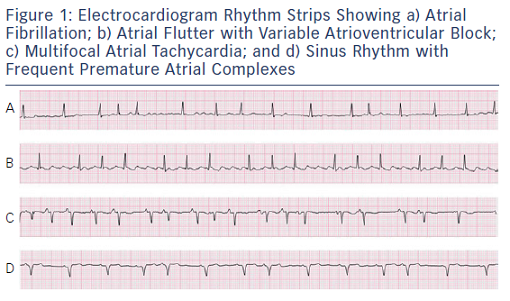

Correlating Symptoms with Rhythm

While patients may present with a variety of symptoms in AF, these may also be noted in a host of other conditions including pulmonary disease, poorly controlled hypertension (or due to the BP medications themselves), obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, or deconditioning.12–14 Therefore, it is important to confirm that the patient’s symptoms are, in fact, related to AF before beginning treatment. This is typically achieved with prolonged rhythm monitoring, ranging from 1 to 30 days depending on the frequency of symptoms. This approach can identify symptomatic bradycardia, prolonged pauses, tachycardia, or simply awareness of conversion into or out of AF. However, it is important to correlate the patient’s symptoms temporally with an episode of AF, as noted in Figure 2. Having episodes of paroxysmal AF on a particular day should not result in symptoms on another day, and concluding that AF produced these symptoms will result in needless testing and therapy. Additionally, an exercise electrogram can be utilized to identify poor rate control or chronotropic incompetence as potential causes for dyspnea on exertion or exercise intolerance. Once the AF and symptoms have been correlated, appropriate therapy can be instituted.15 Anxiety in the presence of palpitations is common; allaying a patient’s fears regarding the arrhythmia and using a systematic approach to treating the risk factors and controlling AF will go a long way toward improving QoL in these patients.16

Lifestyle Modification

In addition to considering pharmacologic or procedural treatment options for AF management, it is important to address modifiable risk factors. Obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and alcohol consumption have all been identified as independent risk factors for the development of AF. Properly evaluating and treating these risk factors may help minimize episodes of AF and also tackle the symptoms.17–21 Caffeine intake has also often been discouraged for patients with AF. However multiple studies have demonstrated no association between caffeine exposure and risk for AF, and there is even evidence to suggest that caffeine consumption in moderate amounts may actually decrease the occurrence of AF.22 Finally, exercise can improve symptoms throughout the spectrum of AF. In fact, multiple studies have demonstrated that exercise training in adults with permanent AF significantly improves rate control (at rest and with exertion), functional capacity, muscle strength, activities of daily living, and QoL.23

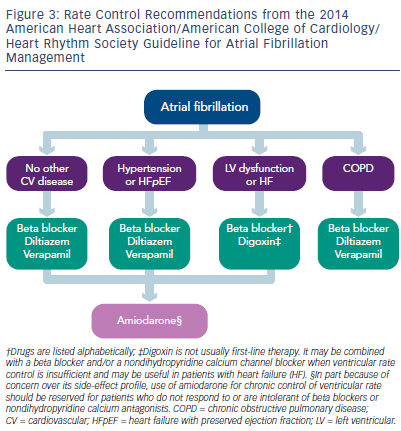

Approaches to Rate Control in Atrial Fibrillation

Controlling heart rate (ventricular response) is a well-established approach to treating patients with minimally symptomatic AF. Beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and digitalis (see Figure 3) are commonly used to accomplish this goal.24,25 The Atrial Fibrillation Follow- up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) trial used 80 beats/ min as a reasonable resting heart rate in AF. More recently, the Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation II (RACE-II) trial compared strict versus lenient rate control and demonstrated that a lenient rate control strategy does not increase morbidity. The criticism levelled against this study is that most patients in the control and treatment groups had heart rates below 90 beats/min and the results were really based on an intention-to-treat analysis.26,27

In active individuals, digitalis is not as helpful for rate control since sympathetic drive during activity can overwhelm the vagotonic action of digitalis. However, it can be useful in conjunction with a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker since it can control ventricular rate without reducing BP. Anti-arrhythmic drugs (AADs), even if they fail to maintain sinus rhythm, can provide rate control without lowering BP. Amiodarone has strong AV nodal blocking activity and may be effective in this application. There is mounting evidence that the hyperpolarization- activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels, responsible for funny current (If) modulation, are also present in the AV node and could be targeted to achieve rate control. The prototypical drug to modulate If in the sinus node is ivabradine.28 Recent case reports highlight the rate- controlling effect of ivabradine in AF through its additional action on the AV node, and this may turn out to be a very useful drug for this purpose, though presently this would be an off-label use of this medication.29–31

The extreme approach in the continuum of rate control is AV node ablation, with pacemaker implantation. This technique has fallen out of favor over the past 20 years due to the rapid incorporation of AF ablation into clinical practice. Nevertheless, AV node ablation with pacemaker implantation remains a very effective technique to control symptoms and improve QoL, particularly in the elderly population, often intolerant of rate-controlling medications.32–33

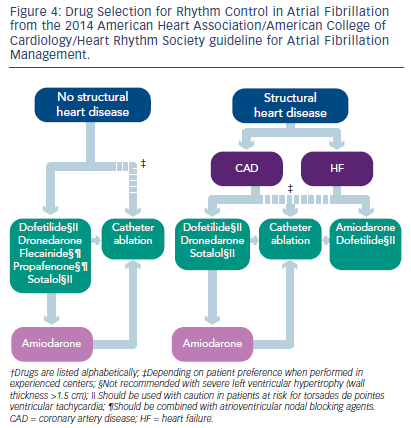

Managing Rhythm Control in Atrial Fibrillation

In patients who are symptomatic from AF, despite good control of heart rate, a rhythm-control strategy should be implemented. Success at maintaining sinus rhythm long-term is highest with good control of underlying risk factors (hypertension, sleep apnea, and obesity). Cardioversion as a means of establishing that AF is responsible for symptoms is a very reasonable first step, even if the long-term success of this approach is only 30–35 %. Once the symptom-rhythm correlation has been established and risk factors have been controlled, AADs may be attempted. The 2014 ACC/AHA/HRS AF guidelines provide a systematic approach to trying AADs (see Figure 4), based on the patient’s co-morbidities.4 Ranolazine in conjunction with dronedarone or ivabradine may also play an important role in effective rate control of AF.30,34 Intolerance of AADs or breakthrough AF while on AADs should prompt consideration of an invasive approach. The specific technique (radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, focal impulse and rotor modulation, laser ablation, or a surgical maze procedure in patients undergoing cardiac surgery) is not as important as the decision to attempt the intervention, and the risks and benefits of this approach need to be discussed with patients in detail. The success rate for all ablative methods for paroxysmal AF has been reported between 66–89 % at 1 year. In long-standing persistent AF, multiple ablation procedures may often be required.35,36

Conclusion

AF should be considered a chronic condition, and like other chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, should be treated with risk factor control and symptom management. Since the morbidity associated with this condition and with the available treatment options is considerable, exhaustive attempts to confirm the diagnosis of AF must be made early. Symptom-rhythm correlation is an important part of this evaluation. Advances in heart rate control, rhythm management, and stroke prevention over the next decade will aid in reducing the burden of AF.