Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is prescribed in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation. An important misconception remains that DAPT should be prescribed to prevent stent thrombosis. Although this may seem obvious, it should be emphasized that the incidence of stent thrombosis is below 1.0 % in second-generation DES and recurrent adverse events are equally attributable to culprit lesions or non-culprit lesions which can also be prevented by DAPT.1,2

Current guidelines recommend at least 12 months of DAPT for patients with ACS who have a low bleeding risk (class 1, level A).3,4 It is advised to treat patients with a low bleeding risk for at least 6 months for stable coronary artery disease (class 1, level A). Optimal DAPT duration remains a matter of debate. Risk assessment is key in this decision, and the higher bleeding risk with longer DAPT duration must be balanced with the benefits of prolonged DAPT duration for patients with increased ischemic risk.3-5

The authors therefore aimed to evaluate current evidence regarding antiplatelet agents, DAPT duration and risk assessment of patients scheduled for PCI with implantation of a latest-generation DES.

Antiplatelet therapy

Thrombocytes, or platelets, are anucleate cell fragments that are essential for primary hemostasis and repair of the endothelium.6 Platelet adhesion, activation and aggregation are considered key elements in the formation of arterial thrombi, and are targets of antiplatelet therapy in the treatment of ACS or DES implantation.7,8

At present, several distinct antiplatelet agents are used in routine practice: aspirin; clopidogrel; prasugrel and ticagrelor.9–11 Aspirin irreversibly inhibits the cyclooxygenase (COX-1) enzyme, reducing the formation of thromboxane A2 and prostaglandins from arachidonic acid, which leads to decreased platelet activation. Several trials have demonstrated that aspirin reduces cardiovascular events.12 However, blocking COX-1 with aspirin also leads to a dose-dependent increased risk of bleeding, mainly in the upper gastrointestinal tract.13

Clopidogrel is the only agent of the purigernic G-protein-coupled P2Y12 receptor inhibitors that is currently recommended for stable coronary artery disease, and is one of the most widely investigated antiplatelet agents. A synergistic effect of clopidogrel on top of aspirin has been established.14 As a prodrug, this thienopyridine requires a two-step oxidation process that contributes to the non-uniform inter-individual clopidogrel response,which has led to high-on platelet reactivity in 30–40 % of patients; this has prompted further research into other potent P2Y12 inhibitors.15

In contrast to clopidogrel, prasugrel requires single-step oxidation by the hepatic cytochrome P450 iso-enzyme family, leading to a rapid-onset, highly potent antiplatelet effect with less variability between individuals than clopidogrel.16,17 Prasugrel should be administered only after the coronary anatomy of a patient has been established, except for those with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), who will undergo primary PCI. Notably, prasugrel is associated with significantly higher rates of TIMI (thrombolysis in MI) major bleeding, life-threatening bleeding and fatal bleeding, and should not be administered to those with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.10

Ticagrelor, as a first-in-class cyclopentyltriazolopyrimidine, can be administered before assessment of the coronary anatomy and acts by reversible and direct inhibition of platelets by allostatic modulation of the P2Y12 receptor, leading to a highly potent, rapid-onset and more predictable antiplatelet effect compared to clopidogrel.11,18 With a plasma half-life of 8–12 hours, ticagrelor requires administration twice daily, which may be unattractive to patients with poor compliance. An important adverse effect of ticagrelor is dyspnea (usually self-limiting), which occurred in roughly 20 % of patients in major trials and accounted for a substantial number of withdrawals.11

Ever since the introduction of DAPT, extensive research has tried to establish the optimal duration of DAPT. This has led the adoption of two main strategies for patients scheduled for PCI: abbreviated, or short DAPT; and prolonged DAPT.

Evidence on Short Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

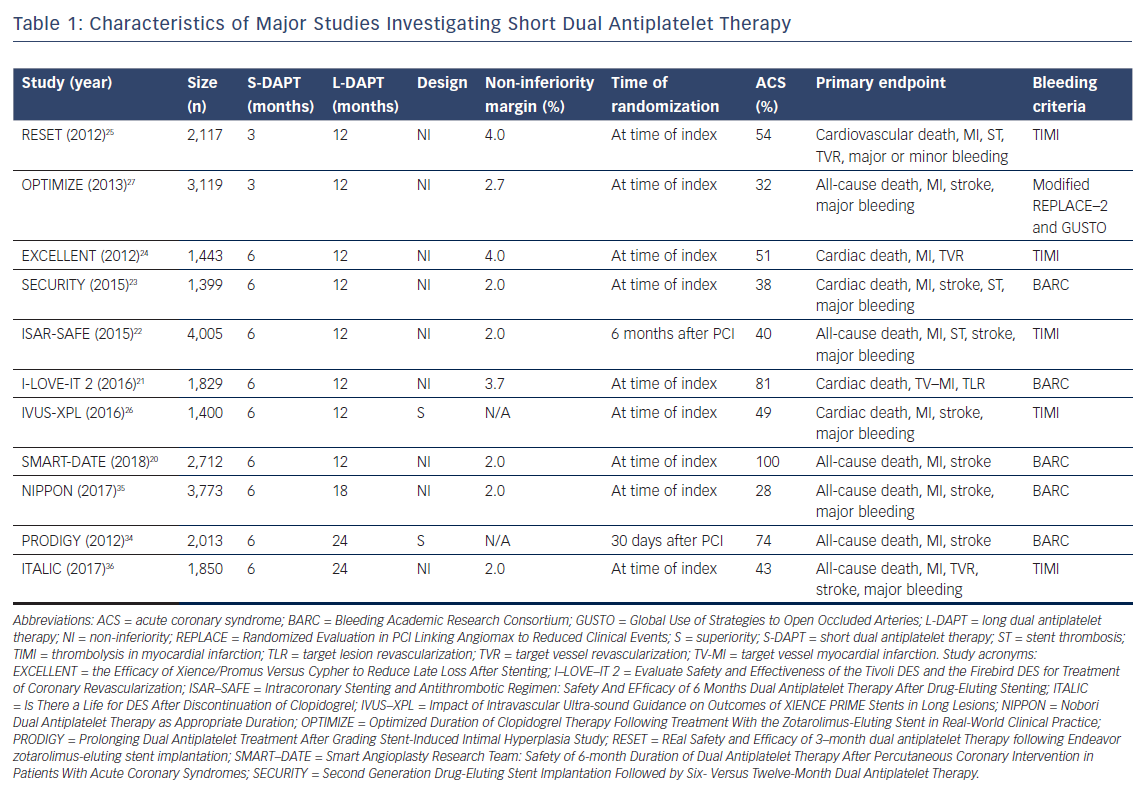

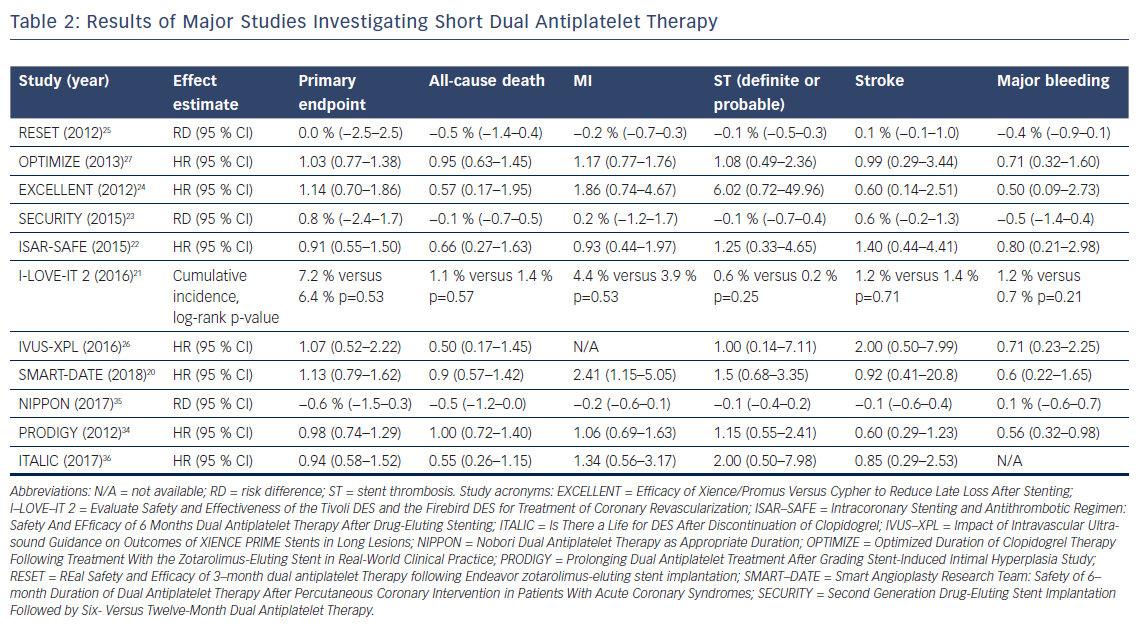

The primary motivators to study short DAPT (S-DAPT; 3–6 months) or ultra-short DAPT (US-DAPT; 3 months or less) are the increased risk of major bleedings caused by DAPT and the improved safety profile of the latest generation DES,which reduces the risks for late and very late stent thrombosis (ST).19 To date, eight trials have investigated S-DAPT (n=6) or US-DAPT (n=2) and compared these to 12 months of therapy (Table 1). All trials demonstrated S-DAPT or US-DAPT to be non-inferior to 12 months of therapy in a comparison of primary composite outcomes (Table 2).20–27

When interpreting the evidence, several aspects should be kept in mind. First, most trials investigating S-DAPT or US-DAPT had a non-inferiority design. Accompanying non-inferiority margins range from 2 % in three trials to up to 4 %,which is rather wide to conclude non-inferiority.20,22–25 Second, the trials were not powered for individual endpoints like ST, but for composite primary endpoints, which were differently composed, complicating interpretation and compatibility. For example, three trials did not include major bleeding in the primary endpoint.20,21,24 Patient selection is the third and probably most important consideration when interpreting different trials. Most trials included a variety of patient groups or at least combined people with stable coronary artery disease and ACS, thereby limiting translation to individual patients. Two trials investigating S-DAPT had stricter inclusion criteria, including only patients with stable angina, silent ischemia or unstable angina or studied only those with biomarker positive ACS.20,23 Overall, mostly patients with a relatively low ischemic risk (stable coronary artery disease or biomarker negative ACS) were included in the majority of these trials. Finally, trials used homogeneous and different bleeding endpoint criteria, which complicates the interpretation of results.

Multiple meta-analyses have attempted to compare the outcomes of trials investigating S-DAPT.28–33 The results of these meta-analyses are consistent and none of them show a difference in mortality. Importantly, the risks for ST, MI and stroke were not increased in the S-DAPT arm, while an increased risk for major bleeding events was observed with 12 months’ treatment.

Three trials compared S-DAPT to prolonged DAPT (>12 months of treatment).34–36 Two trials concluded S-DAPT to be non-inferior to prolonged DAPT, and one trial noted a trend of more complications in the arm who were treated for 24 months.35,36 The only trial powered for superiority did not find 24 months of therapy to be superior to S-DAPT, but did notice a significant increase in BARC 3 or 5 bleeding events (HR 0.56, 95 % CI [0.32–0.98], p=0.037).34

It seems likely that S-DAPT may be beneficial to selected patients with a high risk of bleeding. Major bleeding events are an important complication because of the association between major bleedis and a poor prognosis,in addition to the negative impact these events have on a patient’s quality of life.37 Notably, a recent individual patient data meta-analysis found an association between bleeding-related deaths and DAPT duration after PCI.38 More specifically, S-DAPT was associated with a reduction of bleeding-related deaths compared to long DAPT (L-DAPT; 12 months of treatment) and prolonged DAPT. When interpreting these results, it is important to address the definition used for bleeding-related death, where death was considered to be possibly bleeding related if occurring within 1 year of the bleeding episode, which is a rather liberal definition, leading to an overestimated result. On the other hand, most patients were treated with clopidogrel. With the availability of more potent P2Y12 inhibitors in current practice, the effects on bleeding events or even mortality in these trials may be underestimated. Of course, causality cannot be established, but the impact of bleeding should not be underestimated. More studies have found bleedings associated with an increased risk of recurrent bleeding and all-cause mortality.39,40

Evidence on Prolonged Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

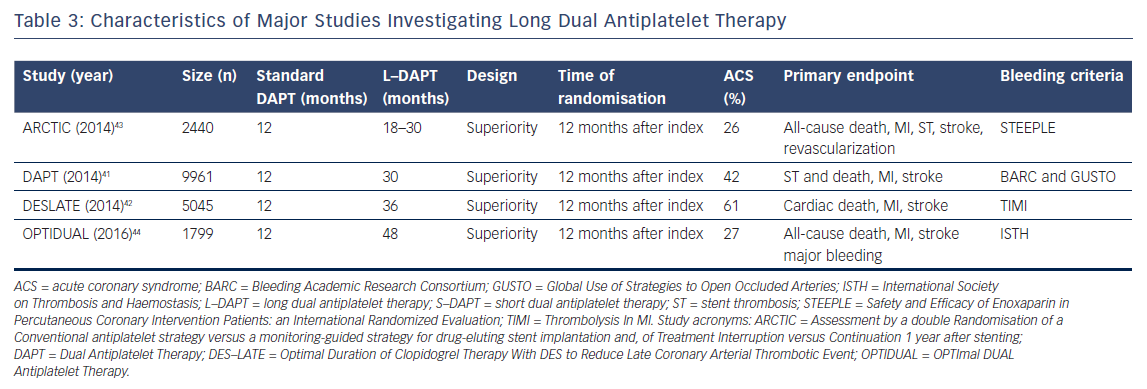

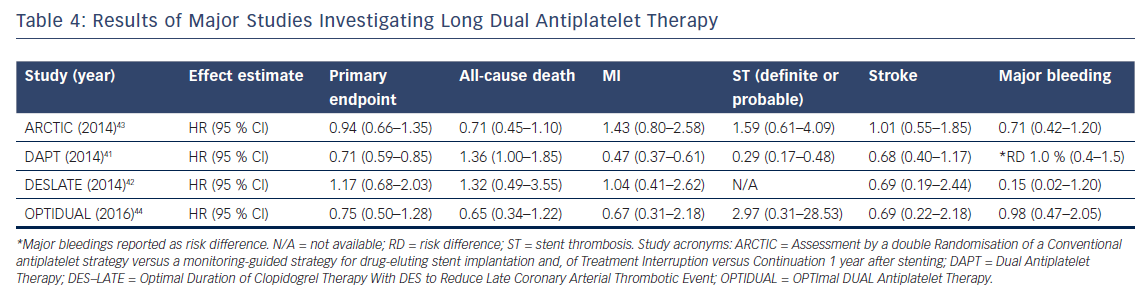

To date, four trials compared prolonged DAPT (>12 months of treatment) to a standard regimen of DAPT (12 months of treatment).41–44 The trials’ characteristics are shown in Table 3, and the main results are summarized in Table 4. The Dual Antiplatelet Trial (DAPT) is the largest study and was powered for superiority for the primary endpoints of definite or probable ST and a composite endpoint of death, MI and stroke.41 For both ST (definite and probable) and the composite primary endpoint, a significant decrease was found when prolonging DAPT (ST: HR 0.29, 95 % CI [0.17–0.48], p<0.001, composite endpoint: HR 0.71, 95 % CI [0.59–0.85], p<0.001). Notably, all-cause deaths were higher in the prolonged DAPT arm (HR 1.36, 95 % CI [1.00–1.85], p=0.05), as a result of to the larger occurrence of non-cardiovascular deaths in the prolonged DAPT arm (HR 2.23, 95 % CI [1.32–3.78], p=0.002). This difference in mortality was explained by a between-group imbalance of patients diagnosed with cancer. Not surprisingly, prolonged DAPT caused an increase in bleeding complications (HR 1.61, 95 % CI [1.21–2.16], p=0.001). In their individual patient data analysis, Palmerini et al.38 observed numerically more bleeding-related deaths in the DAPT trial.

The Assessment by a double Randomization of a Conventional antiplatelet strategy versus a monitoring-guided strategy for drug-eluting stent implantation and of Treatment Interruption versus Continuation 1 year after stenting (ARCTIC)-Interruption trial did not find a difference in the composite primary endpoint (death, MI, ST, stroke or transient ischemic attack, and urgent revascularization).43 However, it should be emphasized that this study was prematurely terminated, and the event rates were lower than anticipated. The prolonged DAPT arm did, however, show a significant increase in STEEPLE (Safety and Efficacy of Enoxaparin in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Patients: An International Randomized Evaluation) bleeding (HR 0.26, 95 % CI [0.07–0.91], p=0.04). Therefore, the ARCTIC-Interruption authors concluded that prolonging DAPT has no apparent benefit and could harm patients. Both the Optimal Duration of Clopidogrel Therapy with DES to Reduce Late Coronary Arterial Thrombotic Event (DES-LATE) trial and the OPTImal DUAL Antiplatelet Therapy (OPTIDUAL) trial did not observe any potential harm from prolonging DAPT nor a beneficial effect.42,44 This is explained by the fact that these studies were powered to detect major differences only.

Several meta-analyses have combined these trials. The results for all-cause death and cardiac death are conflicting.29,30,32,33,45 One showed prolonged DAPT reduced cardiac death,while another indicated non-cardiac death to be increased by prolonged DAPT.29,45 Evidence also showed prolonged DAPT reduced ischemic events at the cost of more major bleedings.29,30,32,33,45 Patients with a high ischemic burden are most likely to benefit from prolonged DAPT or maybe even life-long DAPT.

Patient-tailored Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

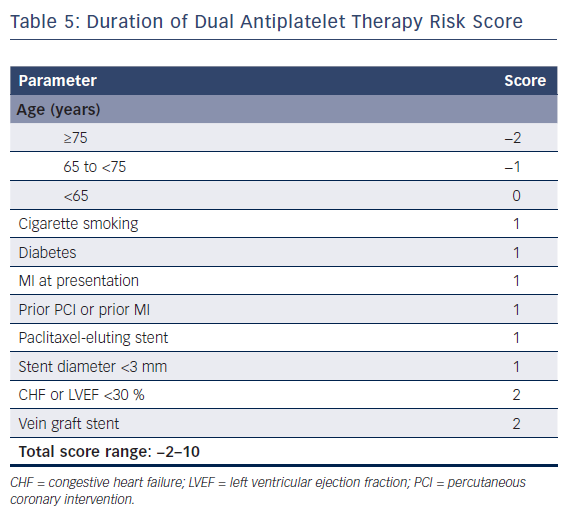

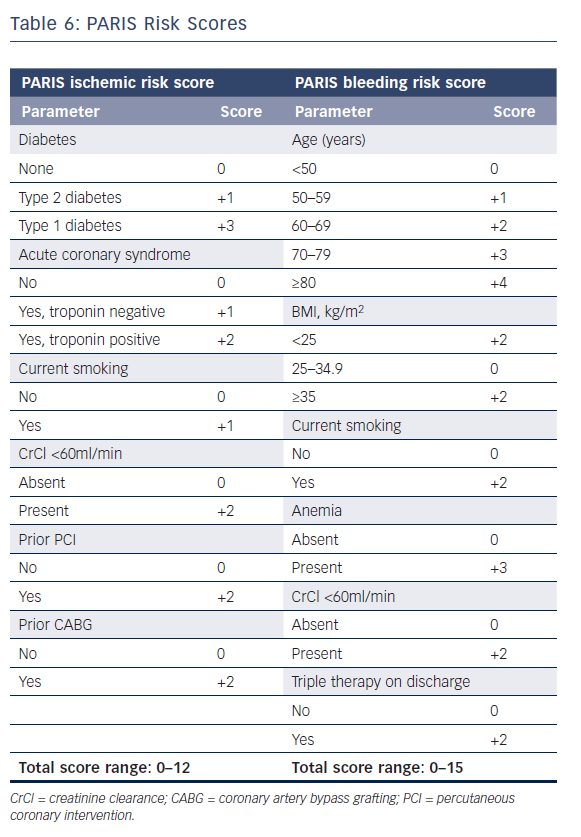

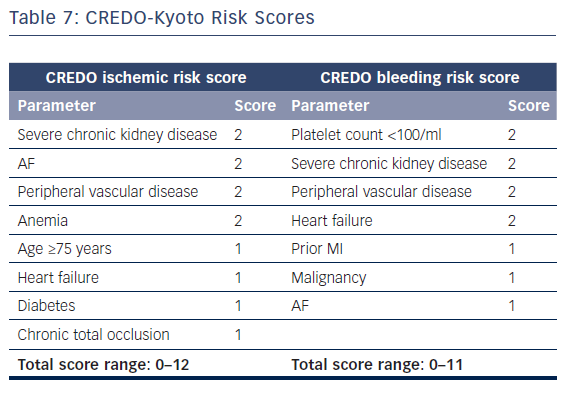

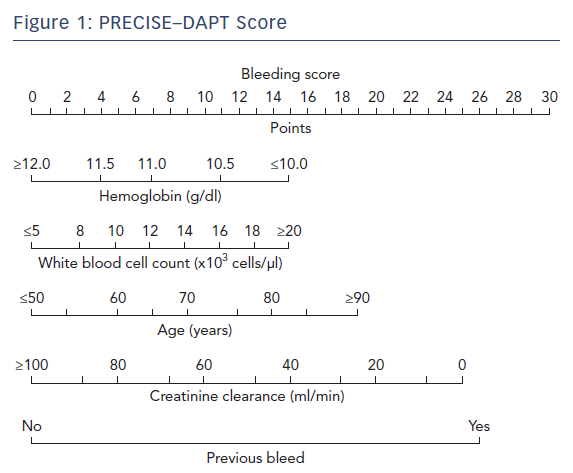

The European Society of Cardiology’s focused update on DAPT3 states that the use of risk scores to guide DAPT duration may be considered (class IIB recommendation). Multiple risk scores to assess a patient’s ischemic or bleeding risk have been proposed: the DAPT score,the PARIS registry risk scores, PRECISE-DAPT, and CREDO-Kyoto (Tables 5–7 and Figure 1).46–49

The first risk assessment tool was the DAPT score,which was derived from the DAPT trial to aid clinical decision-making regarding DAPT duration.46 This score aims to predict who would benefit from prolonged DAPT at 12 months after PCI after an event-free period of 12 months. Including eight variables (age, smoking, diabetes, MI at presentation, prior PCI or MI, paclitaxel-eluting stent, stent diameter, chronic heart failure and vein graft stent), the score ranges from −2 to 10. Any score below 2 is associated with a bleeding risk that exceeds ischemic risk, indicating DAPT cessation at 12 months. High scores (≥2) are associated with an increased ischemic risk, leading to an increased net clinical benefit from continuing DAPT treatment. Important limitations of the DAPT score are: a limited external validity because it is derived from the DAPT study cohort, which included ischemic patients and those who were bleeding event free after 12 months; and the reduced effect when correcting for paclitaxel-eluting stents, which are no longer used.

The PARIS registry risk scores are two scores to predict bleeding and ischemic risk after PCI.47 The ischemic score is composed solely of clinical characteristics (diabetes, ACS type, smoking, creatinine clearance, prior PCI, and prior coronary artery bypass graft), although procedural and angiographic characteristics also influence patients’ ischemic risk.50 The bleeding score includes age, BMI, smoking, anemia, creatinine clearance and triple therapy. Smoking and reduced creatinine increase a patient’s ischemic risk as well as bleeding risk, according to the derivation cohort. Retrospective validation of the PARIS risk scores using data from the platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of DES (ADAPT-DES) registry resulted in moderate discrimination of both the thrombotic and bleeding risk scores.

The PRECISE-DAPT score was developed as a standardized tool to weight bleeding risk before selecting DAPT treatment duration and aims to predict out-of-hospital bleeding events with a five-item score. The external validation in two validation cohorts (PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes [PLATO] and the BernPCI registry) indicated replicable moderate discriminative ability. Its clinical utility is, however, lower than those of other risk scores since the score is primarily based on laboratory results.48

The CREDO-Kyoto risk scores aim to assess thrombotic and bleeding risks using two scores: an eight-item ischemic risk score and a seven-item bleeding risk score.49 Four parameters are included in both scores. This raises questions about clinical applicability, as patients with a high ischemic score are likely to have an increased bleeding score too, leaving the question whether to prolong or shorten DAPT duration unanswered. Unlike other scoring systems, in CREDO-Kyoto, the procedural parameters were tested and included chronic total occlusion in the final ischemic score.

In the first validation studies, the DAPT score was retrospectively replicated in the PRODIGY study, but failed to discriminate the risk on bleeding and ischemic events using data from the ISAR-SAFE cohort.51,52 Hereafter, both the DAPT score and PARIS registry scores were retrospectively validated and compared in a Chinese population (n=5,709).53 Only the DAPT score showed modest accuracy for predicting major bleedings. Both scores showed poor discriminative capacity predicting ischemic events. Therefore, the DAPT score and risk scores from PARIS may not be applicable in a Chinese population. In the Spanish CardioCHUVI (Cardiologia del Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo) cohort (n=1,926),PARIS bleeding score and PRECISE-DAPT score were retrospectively validated.54 For major bleedings, PARIS and PRECISE-DAPT showed a moderate discriminative power and, using decision curve analyses, it was concluded that the PARIS bleeding score had a superior performance. Recently, the DAPT score was successfully validated in a pooled Japanese cohort (n=12,223).55 One year after PCI, the DAPT score successfully stratified ischemic and bleeding risks. However, the investigators observed low ischemic event rates in patients with a high DAPT score. Therefore, questions remain over the clinical utility of the score and the benefit of prolonging DAPT treatment. Last, in a nationwide Swedish registry (n=41,101) the DAPT score had poor discriminative capacity for ischemic events and did not discriminate bleeding risk.35

Results of these validation studies are conflicting, but differences between the validation cohorts need to be taken into account. Cohort size and geographical background in particular may differ substantially between derivation cohorts.

Clinical Perspectives and Future Research

Several randomized trials have established the pivotal role of DAPT following PCI for latest-generation DES implantation. Individual assessment of a patient’s risk profile will be essential to optimize DAPT duration. A substantial proportion of patients have stable coronary artery disease. Especially for stable patients with a low ischemic risk profile, the authors believe short durations of DAPT may be beneficial, given the improved safety profile of currently available DES. On the other hand, it seems obvious that patients with a high ischemic risk profile may need prolonged or even lifelong DAPT.

Regarding the currently available risk scores, any clinical value they add needs to be determined in a prospective randomized trial. Although the authors believe risk scores are likely to improve in aiding individual patient-tailored DAPT, physicians should acknowledge the limitations of existing risk scores, and fully assess the patient’s risk profile and coronary angiographic characteristics. Since optimal durations of DAPT have been investigated for more than a decade, many clinicians believe simplification may be required regarding pharmacotherapy after PCI.

Future research may examine de-escalation of DAPT. For example, the ongoing Ticagrelor With Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients After Coronary Intervention (TWILIGHT) study (NCT02270242) challenges the concept of DAPT as ticagrelor monotherapy for long-term platelet inhibition in a broad population of patients undergoing PCI with DES. As the latest-generation DES with enhanced safety profiles are likely to reduce adverse events even further, a paradigm shift to de-escalation of DAPT should be evaluated in future dedicated trials.